A nerve graft is a surgical method used to repair damaged peripheral nerves by bridging the gap with nerve tissue—either from your own body or a donor—to help restore lost movement or sensation.

Severe nerve injuries can lead to permanent disability if untreated, but timely reconstruction can significantly improve recovery.

On this page we explain how nerve grafts work, who they’re for, the different types available, how surgery is performed, and what to expect during recovery.

What is a nerve graft?

A nerve graft is a surgical technique used to repair a damaged or severed nerve by bridging the gap between two nerve ends with a piece of nerve tissue. This tissue can come from the patient’s own body (autograft) or from a donor (allograft). The graft acts as a scaffold, guiding regenerating nerve fibers (axons) from the proximal stump to the distal end, helping restore sensory or motor function.

Nerve grafting is typically used when:

- The nerve gap is too large to be repaired directly with sutures.

- Tension-free repair isn’t possible.

- The nerve injury involves complete transection or segmental loss.

This approach is most often used for peripheral nerve injuries, such as those affecting the arms, hands, legs, or face. Grafting allows regenerating axons to cross the gap and potentially reconnect with their target tissues, supporting functional recovery over time.

How does a nerve graft work?

A nerve graft works by serving as a physical and biological bridge between the two ends of a damaged nerve. It guides the growth of regenerating axons from the proximal (closer to the spinal cord) end of the injured nerve toward the distal (farther) end, where the nerve used to connect with muscles or sensory organs.

Here’s how the process works:

Harvesting the graft. In autografts, surgeons take a piece of nerve tissue—often the sural nerve in the leg—from the patient. In allografts, donor nerve tissue is used and processed to remove cells that may cause rejection.

Bridging the gap. The graft is sutured between the two ends of the injured nerve. It must match in diameter and orientation to allow proper regeneration.

Axon regeneration. Axons from the healthy nerve end grow into the graft. The internal structure of the graft (endoneurial tubes and extracellular matrix) helps guide them along the correct path.

Reinnervation. As axons reach the distal nerve end, they continue growing toward their original target—such as a muscle or skin receptor. If successful, the nerve can begin to recover its function.

Important considerations

- Time is critical: delayed repair can reduce the chances of meaningful recovery.

- Distance matters: the longer the nerve gap, the more challenging the regeneration.

- Outcomes depend on: age, health status, injury location, and nerve type (motor or sensory).

Nerve grafts do not restore function instantly. Nerve fibers grow at an average rate of 1–3 mm per day, so recovery can take months or even years depending on the injury site.

How does nerve graft surgery restore peripheral nerve continuity?

Nerve graft surgery restores peripheral nerve continuity by bridging the gap between severed nerve ends with a graft. The graft guides regenerating axons from the healthy nerve toward the target tissue, allowing reconnection. This supports the gradual return of sensory or motor function, depending on the nerve involved.

Who is a candidate for nerve graft surgery?

A person may be a candidate for nerve graft surgery if they have a peripheral nerve injury that cannot be repaired through direct suturing due to a gap between the severed ends. In such cases, grafting provides a scaffold for axonal regeneration. Candidacy depends on several clinical factors.

Typical candidates include:

- Patients with complete nerve transection where tension-free repair is not possible.

- Individuals with segmental nerve loss from trauma, tumor resection, or surgical injury.

- Patients with neuromas (painful nerve scars) requiring excision and reconstruction.

- Cases of brachial plexus injury, especially when direct nerve transfer isn’t feasible.

- Facial nerve injuries, often in reconstructive or oncologic surgery.

Factors influencing candidacy:

- Time since injury: earlier intervention improves outcomes; chronic injuries may lead to irreversible muscle atrophy.

- Overall health: patients must be fit for microsurgery and healing.

- Nerve type and function: grafting is often more successful with sensory or mixed nerves than purely motor nerves over long distances.

- Gap length: larger gaps may require nerve allografts or nerve transfers instead.

Patients with nerve damage from penetrating trauma, surgical resection, or certain compressive injuries may benefit from grafting if the anatomy and timing are favorable. In borderline cases, advanced imaging and intraoperative nerve stimulation help determine the best approach.

Which types of nerve grafts are available?

There are several types of nerve grafts used to repair peripheral nerve injuries. The choice depends on the size of the nerve gap, the type of nerve injured, and patient-specific factors. Each type has distinct advantages and limitations in terms of availability, surgical complexity, and outcomes.

1. Autograft (autologous nerve graft)

This is the most commonly used type. Surgeons harvest a piece of the patient’s own nerve—typically the sural, medial antebrachial cutaneous, or great auricular nerve.

- Advantages: no risk of immune rejection; natural structure supports axon growth.

- Limitations: requires a second surgical site; results in permanent sensory loss in the donor area.

2. Allograft (donor nerve graft)

Allografts use processed human donor nerve tissue, such as the Avance® Nerve Graft. These grafts are decellularized to minimize immune response.

- Advantages: no donor-site morbidity; available in multiple lengths and diameters.

- Limitations: higher cost; may have reduced efficacy in long or complex injuries.

3. Synthetic nerve conduits (bioengineered tubes)

These are artificial tubes made of materials like collagen or polyglycolic acid, used to guide nerve regeneration across short gaps.

- Advantages: no donor tissue required; less invasive.

- Limitations: best for small gaps (<3 cm); limited success in motor nerve repair.

4. Vascularized nerve grafts

These involve transplanting nerve tissue with its blood supply intact, used in complex reconstructions or scarred surgical fields.

- Advantages: enhanced healing in compromised tissue beds.

- Limitations: technically demanding; limited to specialized cases.

5. Conduits with growth factors or stem cells (experimental)

Some advanced grafts incorporate biological agents to promote faster or more complete regeneration.

These graft options are selected based on gap length, nerve function (sensory vs. motor), timing of surgery, and the need to minimize donor-site morbidity.

What is an Avance nerve graft and when is it used?

An Avance nerve graft is a processed human nerve allograft used to repair peripheral nerve injuries. It’s decellularized to reduce immune response while preserving internal structure. Surgeons use it for short-to-moderate nerve gaps when autografts aren’t feasible or to avoid donor-site complications. It’s commonly used in hand and facial repairs.

How is nerve graft surgery performed?

Nerve graft surgery is a microsurgical procedure that involves bridging a gap between two ends of a damaged peripheral nerve using a segment of nerve tissue. The goal is to guide axonal regrowth across the gap and restore function. The procedure is typically done under general anesthesia by a plastic, orthopedic, or neurosurgeon trained in peripheral nerve reconstruction.

Step-by-step overview of the procedure:

Surgical exposure of the damaged nerve. The surgeon identifies and exposes the injured nerve through an incision. Both the proximal and distal ends are carefully evaluated.

Debridement of the nerve ends. Damaged or scarred tissue is trimmed back to healthy fascicles to ensure the graft is connected to viable nerve tissue.

Selection and preparation of the graft.

- Autograft: a sensory nerve (e.g., sural nerve) is harvested from the patient’s leg or arm.

- Allograft: a pre-processed donor graft is selected based on size and length.

- The graft is cut to bridge the nerve gap without tension.

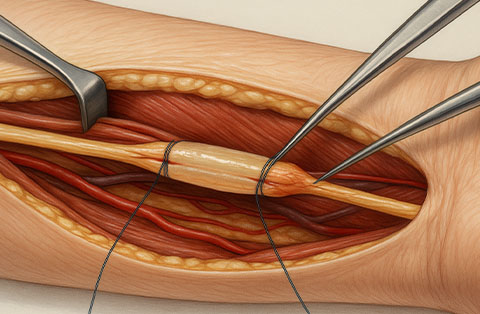

Microsurgical coaptation. Using an operating microscope, the surgeon sutures the graft to the two nerve ends with ultra-fine, non-absorbable sutures. Fibrin glue may be used to reinforce the repair.

Alignment and orientation. Proper alignment of fascicles is crucial for functional recovery; motor and sensory pathways are aligned when possible.

Closure and dressing. The incision is closed in layers. A splint or dressing is applied to immobilize the limb and protect the graft.

Surgical considerations

- Tension-free repair is critical for success.

- Graft diameter and length must match the defect accurately.

- Intraoperative nerve stimulation may be used to assess viability.

Post-surgical recovery focuses on protecting the repair site, maintaining joint mobility, and initiating a monitored rehabilitation plan. Success depends on several factors, including the distance axons must regrow, the patient’s age, and how soon the repair is performed after injury.

What are the differences between nerve graft surgery and nerve transfer?

Nerve graft surgery bridges a nerve gap using a graft to guide axon growth across the injury. Nerve transfer redirects a nearby healthy nerve to reinnervate a target muscle or area. Transfers are often faster and used when grafts aren’t viable due to long gaps or delayed treatment.

How long is recovery after nerve graft surgery?

Recovery after nerve graft surgery is gradual and depends on the distance nerves must regenerate, the location of the injury, and the patient’s overall condition. Full recovery may take several months to over a year.

Key timelines in recovery:

- Immediate postoperative period (0–2 weeks): focus on wound healing and preventing complications; the operated limb is often immobilized.

- Early regeneration phase (2–12 weeks): axons begin to grow from the proximal end into the graft at about 1–3 mm per day.

- Functional recovery phase (3–12 months or longer): as axons reach the distal nerve and targets, some function returns; motor recovery usually lags behind sensory.

Factors that influence recovery time:

- Injury location: proximal injuries take longer than distal ones.

- Nerve type: sensory nerves often recover faster than motor nerves.

- Length of the graft: longer grafts require more time for axons to reach the target.

- Patient factors: age, metabolic health, smoking status, and rehab adherence.

Even with optimal treatment, not all patients regain full strength or sensation. However, early surgical repair combined with structured rehabilitation improves the chances of meaningful functional recovery.

What therapies and follow-up care help recovery after nerve surgery?

Recovery after nerve surgery involves physical therapy, occupational therapy, and regular follow-up. Therapies focus on maintaining joint mobility, preventing muscle atrophy, and retraining motor and sensory functions. Electrical stimulation, splinting, and sensory re-education may also be used. Regular monitoring tracks nerve regeneration and adjusts care as needed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a nerve graft do?

A nerve graft acts as a bridge between the two ends of a damaged nerve. It guides regenerating axons across the injury site, helping restore connection to muscles or skin. This supports the recovery of movement or sensation, depending on the function of the repaired nerve.

How long does it take to recover from a nerve graft?

Recovery from a nerve graft typically takes 6 to 12 months, depending on the location and length of the injury. Nerves regenerate at about 1 mm per day, so longer distances require more time. Full recovery may take over a year, especially for motor nerves or proximal injuries.

What is the success rate of nerve grafting?

The success rate of nerve grafting varies based on injury type, location, and timing. Sensory nerve grafts have success rates around 70–90%, while motor nerve recovery is lower, often 50–70%. In one study of 385 nerve repairs, including sensory, mixed, and motor nerves, about 82% achieved meaningful functional recovery. Early surgery, short graft length, and proper rehabilitation improve outcomes. Complete functional return isn’t guaranteed in all cases.

What is a cross-facial nerve graft?

A cross-facial nerve graft is a surgical technique used in facial nerve reconstruction. Surgeons take a nerve graft—usually the sural nerve—and connect it from the healthy facial nerve side to the paralyzed side. It delivers motor axons across the face, enabling reanimation of facial muscles on the affected side.

What are the nerve graft donor sites?

Common nerve graft donor sites include the sural nerve (leg), medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (forearm), and great auricular nerve (neck). These nerves are typically sensory, so harvesting them causes minimal functional loss. The choice depends on graft length needed, donor-site accessibility, and minimizing morbidity.