Asymmetric crying facies causes uneven facial movement in newborns. Early diagnosis helps rule out related conditions and guides treatment to improve facial balance and overall development.

What is asymmetric crying facies syndrome?

Asymmetric crying facies syndrome (ACF) is a congenital condition. It affects the movement of the lower lip during crying. The lower lip pulls unevenly when the baby cries, usually due to underdevelopment or absence of the muscles that control lip movement. The most commonly affected muscle is the depressor anguli oris muscle.

This condition is often noticeable at birth. The face appears symmetrical when the baby is resting. However, when the baby cries, one corner of the mouth does not move downward like the other side. This creates a lopsided appearance.

ACF is not typically associated with pain or discomfort. In many cases, it is an isolated finding. However, it can sometimes be linked to other congenital abnormalities, especially involving the heart, head, or neck. Early diagnosis is important to rule out other underlying conditions.

What is Congenital ACF (CULLP)?

Congenital asymmetric crying face is also called congenital unilateral lower lip palsy (CULLP). It means one side of the lower lip does not move well. This happens because the muscle that pulls the corner of the mouth down is weak or missing on one side.

This condition shows up at birth. The baby’s face looks normal when resting. When the baby cries, one side of the mouth moves down, but the other side does not. This causes an uneven look.

Most babies with CULLP do not have problems with feeding or speech. In some cases, the muscle improves over time. In other cases, the difference stays the same as the child grows.

What causes the asymmetrical crying face?

Asymmetric crying facies happens when part of the lower face does not move the same way as the other side during crying. This usually affects newborns and often results from problems in the muscles or nerves that control the lower lip.

Causes of asymmetric crying face:

Underdeveloped or missing depressor anguli oris muscle on one side

Birth trauma affecting the facial nerve

Pressure during delivery causing temporary nerve weakness

Genetic factors affecting muscle or nerve development

Part of a syndrome with other birth defects

Rare cases of nerve damage due to infection or other conditions during pregnancy

Are there associated congenital anomalies?

Yes, some babies with asymmetrical crying facies syndrome have other congenital anomalies. Studies show that up to 70% of affected infants may have additional abnormalities. These are usually linked to structures that develop around the same time in the womb.

Common associated anomalies include:

Heart defects such as ventricular septal defect or tetralogy of Fallot

Neck and facial structure differences

Ear abnormalities or hearing issues

Spine or limb anomalies

Genetic syndromes such as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome or CHARGE syndrome

Doctors often recommend further tests, such as heart ultrasound or genetic evaluation, to check for related conditions. Early diagnosis helps guide proper care.

What are the symptoms of asymmetric crying facies?

Asymmetrical crying facies shows clear signs when the baby cries or makes facial expressions. The most noticeable symptom is the uneven movement of the lower lip. The face usually looks normal when the baby is calm or not moving the facial muscles.

One corner of the mouth does not move downward when crying

Lower lip pulls more to one side

Face appears symmetrical at rest

Normal movement of eyes and forehead

No drooping of the eyelid or eyebrow

May include feeding difficulties in rare cases

Possible signs of other birth defects in some babies

How is asymmetrical crying facies diagnosed?

Doctors usually diagnose asymmetric crying facies during a physical exam shortly after birth. They observe the baby’s face while crying. The uneven movement of the lower lip often gives a clear sign of the condition.

To confirm the diagnosis and check for related problems, doctors may use the following tests:

Physical examination of the face and muscles

Crying or facial movement observation to assess asymmetry

Ultrasound of the face or neck to check the muscle structure

Echocardiogram to look for heart defects

Hearing test if ear anomalies are present

Genetic testing if a syndrome is suspected

These tests help rule out other causes and detect any associated anomalies.

What are the potential treatments for facial palsy associated with acf?

Treatment for facial palsy linked to asymmetric crying facies (ACF) depends on the cause and severity. Many cases are mild and do not need any treatment. If the facial asymmetry is due to underdeveloped muscles and no other health issues are present, doctors usually recommend observation. Some children improve over time as facial muscles grow.

If the condition affects function or is linked to other problems, treatment may include:

Observation and monitoring

Most babies with ACF do not have serious functional problems. Doctors monitor growth and development. They check for speech, feeding, and emotional expression. If the child meets milestones and has no related conditions, no further treatment is needed.

Physical therapy

Facial exercises may help improve muscle coordination and strength. A therapist teaches parents how to help the baby move facial muscles through gentle exercises.

Surgical treatment

If the asymmetry is severe or persistent, surgery may be considered. Surgical options include:

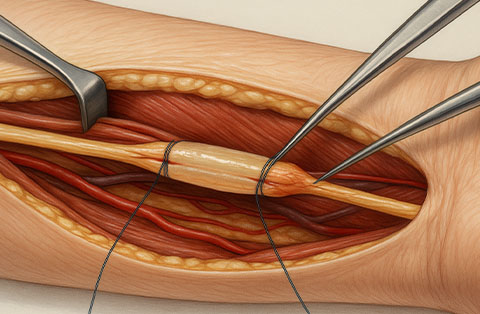

Muscle transfer: Surgeons move a small muscle from another part of the body to the face to improve symmetry.

Nerve grafting: If a damaged facial nerve causes the problem, surgeons may reconnect it using a nerve graft.

Cosmetic procedures: Minor procedures may improve appearance in older children or teenagers.

Treatment of associated conditions

If the child has heart defects, ear problems, or genetic syndromes, those need separate treatment. Multidisciplinary care may involve cardiologists, geneticists, or ENT specialists.

In summary, treatment is personalized. Most children with ACF lead normal lives without intervention. For more complex cases, early evaluation and a tailored care plan give the best outcome.

Can facial paralysis be corrected?

Yes, facial paralysis can often be corrected or improved, depending on the cause and severity. In cases related to asymmetric crying facies, many children have mild symptoms and may not need any treatment. If the paralysis affects function or appearance, treatment options are available.

Options to correct facial paralysis include:

Physical therapy: Strengthens facial muscles and improves movement

Facial muscle exercises: Helps improve control and balance

Surgical procedures:

Muscle transfer surgery to restore movement

Nerve grafting or nerve transfer to restore nerve signals

Cosmetic surgery to improve facial symmetry

Early diagnosis and treatment planning improve results. In many children, the condition remains mild and stable without intervention.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Cayler syndrome?

Cayler syndrome is a rare condition that causes facial asymmetry when a baby cries. It results from the absence or weakness of a lower lip muscle on one side. The face looks normal at rest. Cayler syndrome is often linked to heart defects and genetic conditions, especially 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Early diagnosis helps guide proper care.

Is there a link between cayler syndrome and heart defects?

Yes, Cayler syndrome is often linked to heart defects. Many babies with this condition have congenital heart problems. The most common defects include ventricular septal defect and tetralogy of Fallot. These heart issues may appear as part of a genetic syndrome. Doctors usually check the heart with an echocardiogram when they suspect Cayler syndrome.

What are the symptoms of Cayler syndrome?

Cayler syndrome causes the lower lip to pull unevenly when the baby cries. One corner of the mouth does not move downward. The face looks normal at rest. Other symptoms may include heart defects, ear shape differences, or feeding issues. Some babies may also show signs of a genetic condition like 22q11.2 deletion syndrome.

Is asymmetric crying facies rare?

Asymmetric crying facies is not very rare. It affects about 1 in every 160 live births. Many cases go unnoticed because the face looks normal when the baby is not crying. Doctors often find it during routine newborn exams. Some cases are isolated, while others may be linked to other congenital conditions.

Can neonatal asymmetric crying facies go away on its own?

Yes, neonatal asymmetric crying facies can improve on its own. In some babies, the facial muscles strengthen over time. The asymmetry becomes less noticeable as the child grows. Most cases do not cause long-term problems. Regular check-ups help track progress. If the condition does not improve, doctors may suggest further evaluation or treatment.

What is the prognosis for children with congenital acf?

The prognosis for children with congenital ACF is usually good. Most children grow and develop normally. If the condition is isolated, it often does not affect speech, feeding, or expression. Some cases improve over time. When linked to other conditions, the outcome depends on the severity of those issues. Regular follow-up helps guide care.